- Winter Rapeseed (40 ha total): “Annabella” – 25 ha, “Akilah” – 15 ha

They survived! Surprisingly, everything was fine with the winter rapeseed, as my experiment in growing them in the cellar indicated. The severe cold somehow showed me remorse. Did I do something right? I don’t think so; it was more likely just luck. Unfortunately, many farmers in Western and Southern Estonia were not as fortunate, and their winter rapeseed experienced varying degrees of damage, not to say they were destroyed.

Even though “Annabella” was sown nearly 10 days earlier than “Akilah,” the first-sown fields were already poor when they emerged. I suspect dry soil and some unknown factor as the reasons. Despite the long autumn, some of the sown seeds still did not start growing.

- Winter Barley (18 ha “Wallace”): Another surprise, the field emerged from under the snow looking nice and green, with winter damage only in areas where water had stayed too long.

However, not all farmers experienced the same outcome. Just like with winter rapeseed, there was also winter barley damage in the same regions.

- Winter Wheat (90 ha total): Hybrid wheat “Hyacinth” – 5 ha, “Informer” – 85 ha Although I made a few mistakes with the hybrid wheat (later and deeper sowing; it should be sown 5 days before conventional varieties and at a depth of up to 2 cm for better tillering), the two small fields survived the winter well, and the fields that emerged from the snow showed good potential.

For the conventional variety “Informer,” 17 ha were very good, but on the remaining 73 ha, there were both major and minor winter damages – mainly because water had stayed in some hollows for too long. It didn’t come to re-sowing, but there was no longer hope for a super yield.

Winter Crops Fertilization

Although I boasted about how I wanted to start fertilizing immediately when the law allows (March 21), the first granules actually went on the field on April 9. Why? Surprise, surprise, but the cold and wet spring didn’t allow starting earlier; the fields simply couldn’t support the machinery. As if weather has never interfered with agriculture before! 😀

With the first round, as has become my habit in recent years, I applied NPK and then nitrogen fertilizer on the same day. Although I would have liked to apply the second round of nitrogen fertilizer within a couple of weeks, the weather played tricks again. Meanwhile, it snowed, it was very cold, then suddenly it warmed up, sowing began, and I managed to start fertilizing again on May 14.

At that point, the winter rapeseed had already started to bud, and there was a small fear that this could reduce yield. However, upon visual inspection, I did not detect any mechanical damage. I set the fertilizer spreader to the maximum height and at recommended angle so that the fertilizer would “fall” into the field rather than fly horizontally.

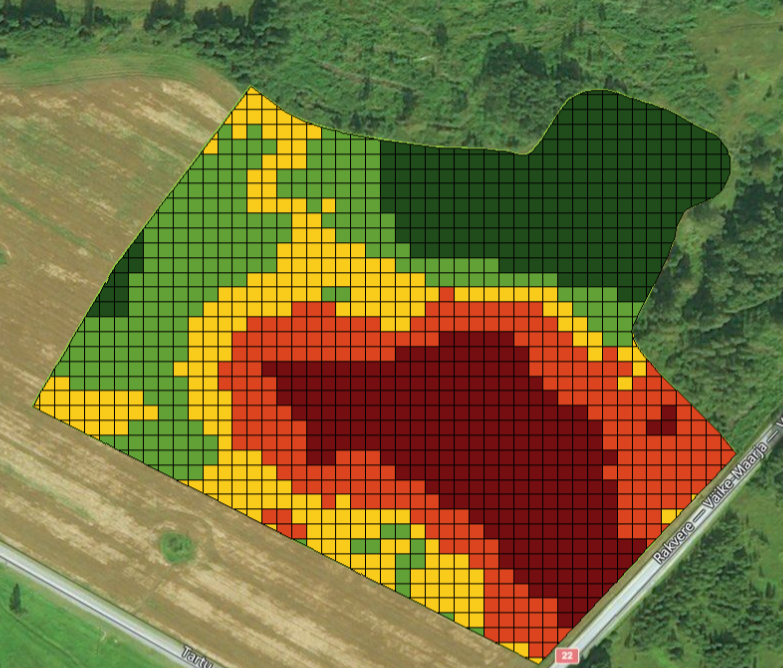

I apply NPK fertilizers according to fertilization maps and the first round of nitrogen based on yield maps from previous years. The second round of nitrogen is applied according to maps made with Yara AtFarm satellites, which I, of course, modify based on my own intuition and experience.

If there’s a bare spot, it’s not worth putting 100 kg of nitrogen there; it won’t fill the hole. If there’s little vegetation, I reduce the amount by up to 90% or even 100% if it’s empty.

Numbers!

Next, I’ll break down the yield expectations and nitrogen amounts per crop and comment on why the amounts are as they are:

- Winter Rapeseed – Expecting 3 t/ha, with a nitrogen level including autumn at 130-139 kg. The “Annabella” fields looked poor already in the autumn and didn’t improve over the winter. The hope was that a good spring would help the rapeseed plants develop additional branches. The “Akilah” field was very nice, despite being sown directly after peas, which is generally not recommended due to common diseases.

Since the potential of the “Annabella” fields is rather average and the “Akilah” field benefits from nutrients left by the peas, I didn’t apply 150 or even 160 kg of nitrogen to these fields. I don’t believe that a higher nitrogen amount would bring me a higher yield.

- Winter Barley – Expecting 6 t/ha, with a nitrogen level including autumn at 109 kg.

This field N level determination is actually very simple; it’s an area with unprotected groundwater, and it’s not allowed to apply more than 120 kg of nitrogen per hectare per year. Additionally, the winter barley was sown after peas, which also add nitrogen to the soil, and the actual fertilization need for a six-ton per hectare yield is indeed 110 kg of nitrogen.

- Winter Wheat – Expecting 4.5 to 8 t/ha, with a nitrogen level including autumn at 118-170 kg/ha.

Here, I varied the amount of nitrogen applied significantly based on the fields’ potential in previous years, moisture regime, and the extent of winter damage.

For the hybrid wheat, I limited myself to just 136 kg of nitrogen and did only one round of NPK + nitrogen fertilization in the spring. It’s interesting to test what the hybrid wheat can do when given enough nitrogen for a 6-ton yield. According to reports, a better root system should produce a higher yield with less nitrogen, even in drought conditions.

Some of the wheat fields were sown after peas, some after winter rapeseed, and one field was sown after wheat. These different previous crops resulted in varying nitrogen levels.

Overall, the economic situation in recent years has made me strive more to avoid the “same amount of fertilizer for every field” principle. Efficiency is crucial for a small farm like mine, and a few days spent creating maps do not outweigh the cost of wasting money.